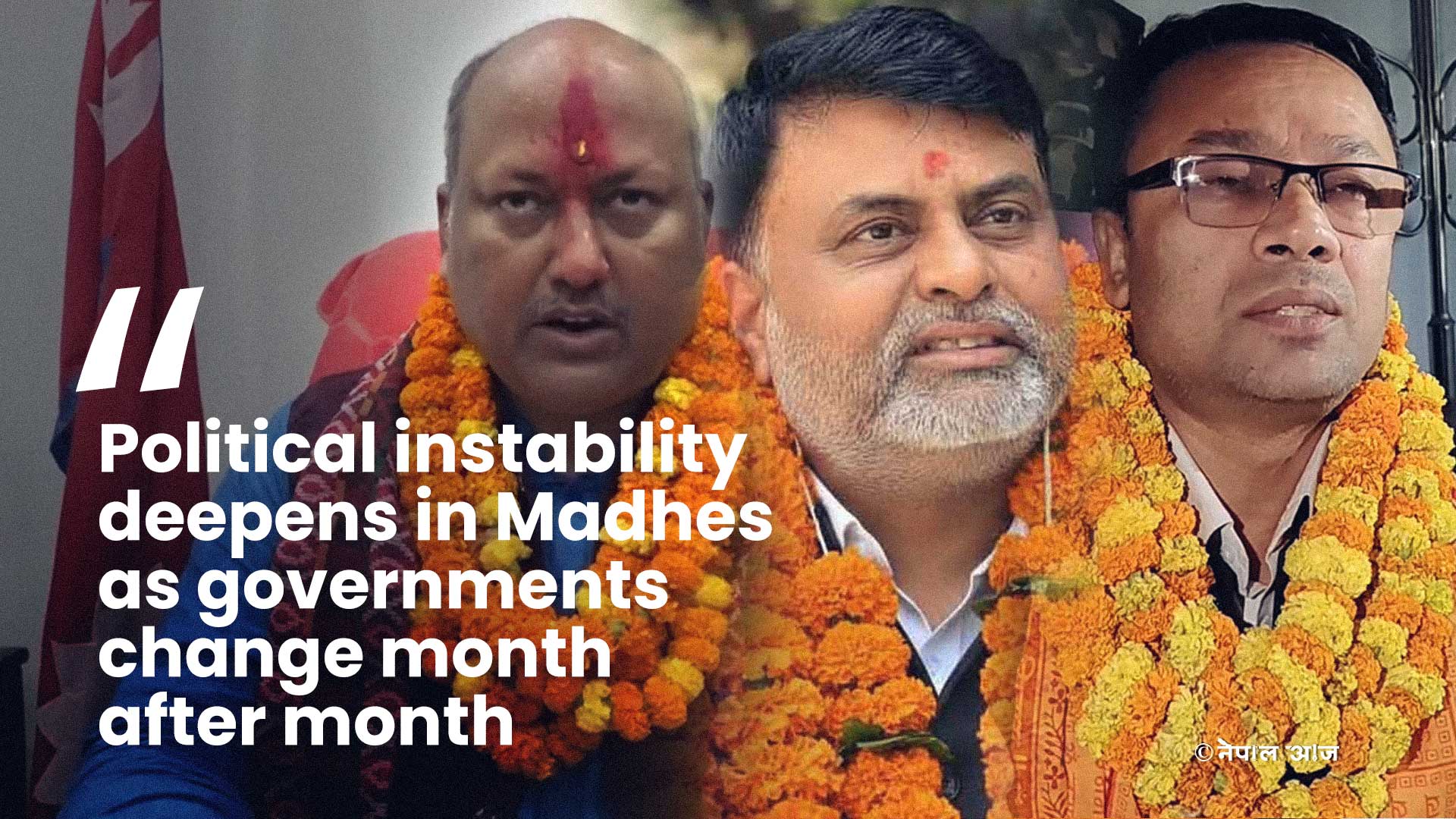

After Three Chief Ministers Fall, Madhes Faces a Full-Blown Stability Crisis

Madhes Province has entered a new phase of political uncertainty after three chief ministers were removed within just two months, reigniting long-standing questions about the durability of provincial governance in Nepal. On 29 Asoj 2082 (mid-October 2025), Satish Kumar Singh lost his position after failing to secure a vote of confidence; on 22 Kartik 2082, the government led by Jitendra Prasad Sonal collapsed not through resignation but due to a sudden reversal in power alignment; and on 18 Mangsir 2082, CPN–UML’s Saroj Kumar Yadav was forced to step down after being unable to obtain a vote of confidence within the 24-hour deadline issued by the Supreme Court. The rapid turnover of three governments within two months has underscored how deeply the province remains trapped in a cycle of fragile power arithmetic rather than stable governance.

Singh, who became Chief Minister on 25 Jestha 2081 through multi-party support, stepped down on 29 Asoj 2082 amid the political heat of the Gen-Z movement, internal party dissatisfaction, and shifting coalition pressures. His abrupt exit, against the backdrop of mounting youth calls for greater accountability, fueled criticism that political responsibility in Madhes is still more rhetorical than real.

Following Singh’s departure, coalition partners named Jitendra Prasad Sonal as Chief Minister on 22 Kartik 2082. But before his government could take root, the power balance shifted again. When CPN–UML presented its numerical claim in the Provincial Assembly, Saroj Kumar Yadav was appointed Chief Minister on 23 Kartik 2082, automatically displacing Sonal. The episode exposed the growing complexity of Madhes politics, where governments fall not due to electoral outcomes but due to minute-to-minute rearrangements of alliances.

Yet Yadav’s administration also proved short-lived. After opposition parties raised constitutional objections to his appointment, the Supreme Court ordered on 2 Mangsir 2082 that he secure a vote of confidence within 24 hours. Intense polarization, factional distrust, and procedural disputes inside the Assembly made compliance nearly impossible, leading Yadav to resign on 18 Mangsir 2082. The chain of departures reinforced a widespread sentiment: in Madhes, stability survives only in political speeches, not in practice.

The turbulence in Madhes is not merely a sequence of leadership changes but a symptom of deeper structural dysfunction. Persistent inter-party conflict, ad-hoc coalitions, unclear power-sharing between federal and provincial tiers, and repeated disruptions in policy continuity have left the provincial administration mired in uncertainty. Every change of government halts crucial decisions, suspends development projects, and weakens the delivery of essential public services—further eroding public trust in the institutions meant to serve them.

The Gen-Z movement had challenged Nepal’s old political class and demanded a new culture of accountability. But with three successive governments collapsing within weeks, young voices in Madhes increasingly argue that meaningful change must be reflected not only in street protests but in stable, functional governance.

Coalition negotiations are once again underway in the Provincial Assembly. But for citizens, the central question remains unchanged: why must they continue paying the price for political instability they did not create?

Madhes be victorious,

May Nepal prosper.

![From Kathmandu to the World: How Excel Students Are Winning Big [Admission Open]](https://nepalaaja.com/img/70194/medium/excel-college-info-eng-nep-2342.jpg)