Fear Spreads Alongside Party Flags? Security Anxiety Surges in Village After Oli’s Arrival

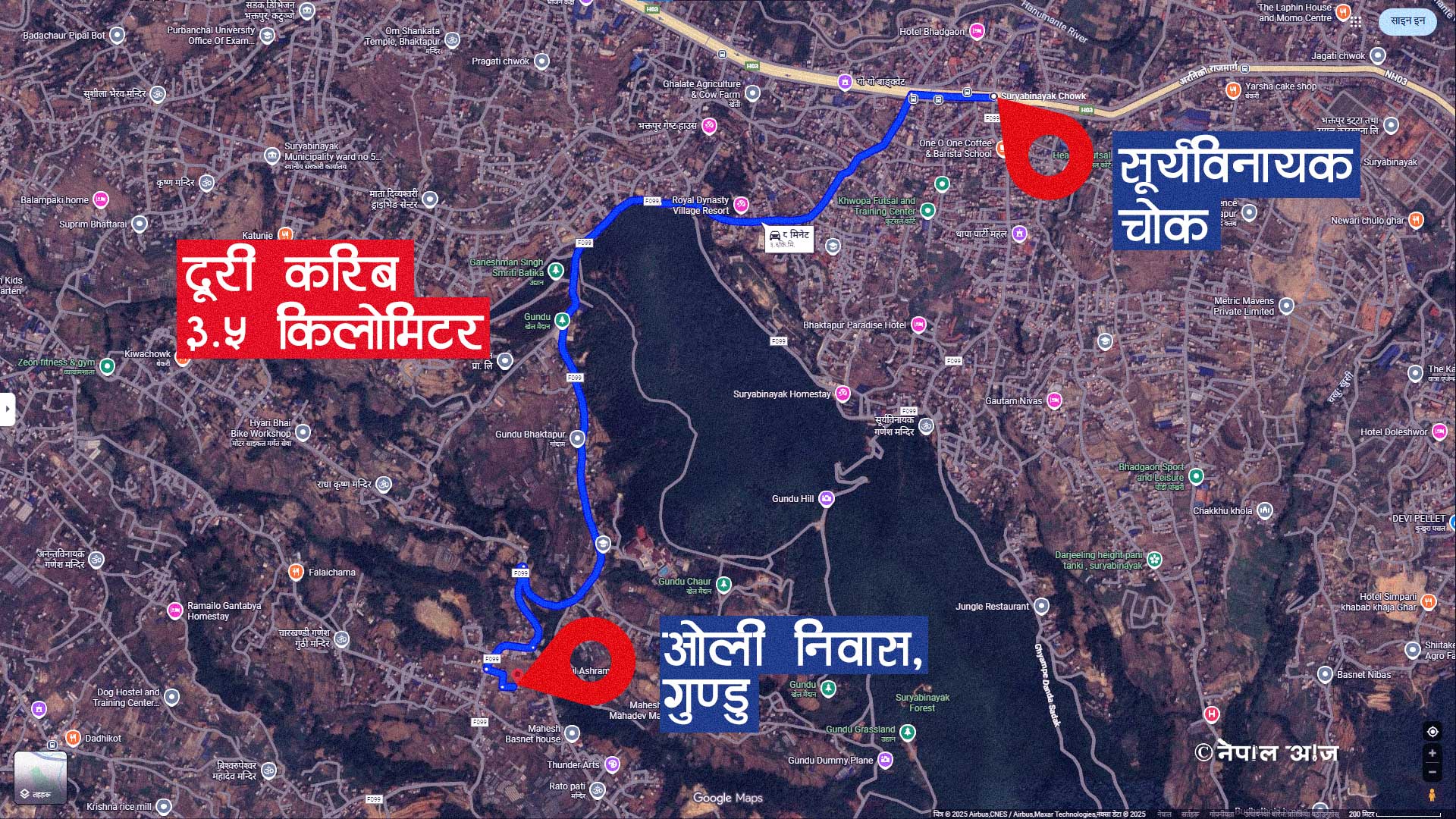

As the smoke and memories of the Gen-Z uprising — which saw parts of Singha Durbar and private properties set ablaze — still linger in the public mind, the quiet village of Gundu, located about 12.5 kilometers from the protest epicenter and 3.5 kilometers north of Suryabinayak Chowk, has entered an unusual state of tension. The atmosphere shifted abruptly after former Prime Minister KP Sharma Oli, who was ousted following the unrest, relocated to a private residence in the village. What was once considered a peaceful area outside the capital has suddenly become a focal point of political sensitivity and security concern.

In Gundu-7 of Suryabinayak Municipality, near Tithali Ganesh–Bhairav, a new security gate has been installed on the auxiliary road leading off the main route for Oli’s protection. There was no gate in the past; it appeared only after his arrival. His residence lies roughly 130 meters inside from this newly placed checkpoint.

Across the village, the question “Could it all happen again?” echoes in hushed conversations, though most residents decline to speak on camera. The violent scenes of arson and clashes during the Gen-Z movement remain vivid, and that collective memory makes the nights in Gundu feel heavier. Some residents say the UML party flags appearing along the roadside signal not just political presence but the possibility of gatherings — a development they fear could escalate into renewed confrontation.

Unlike Kathmandu, Gundu is a small, tightly-knit community where nearly everyone knows each other. In such an intimate social setting, the relocation of a leader at the center of national controversy has amplified psychological pressure. One resident, requesting anonymity, remarked, “We don’t want politics — we want peace. If crowds return, our lives and property could be at risk.”

While a few villagers admit they are pleased that their village is suddenly “known,” many others feel uneasy. They describe Oli’s recent public remarks as “irresponsible and bombastic,” saying his statements have intensified anxiety rather than calming tensions. Another villager, also speaking anonymously, put it bluntly: “His words double our fear during the day and quadruple it at night.” For locals who have already lived through the trauma of violent unrest, such rhetoric only deepens psychological wounds.

Oli’s office has not issued any formal response to these concerns. Efforts to contact his secretariat for comment were unsuccessful. However, a local administrative official, speaking informally, said, “We are assessing the situation. There is no immediate threat, but sensitivity remains high.” The gap between the authorities’ cautious reassurance and the worried faces of residents reveals the true emotional landscape of Gundu at the moment.

Though there is little visible political activity in the village, the pervasive climate of fear has placed the community under invisible strain. The expectation among residents is simple: they hope politics does not erupt again, words do not ignite new fires, and their village remains peaceful. Otherwise, it may not take long before the shadow of nationwide unrest once again engulfs this small settlement.

KP Sharma Oli Gundu

![From Kathmandu to the World: How Excel Students Are Winning Big [Admission Open]](https://nepalaaja.com/img/70194/medium/excel-college-info-eng-nep-2342.jpg)