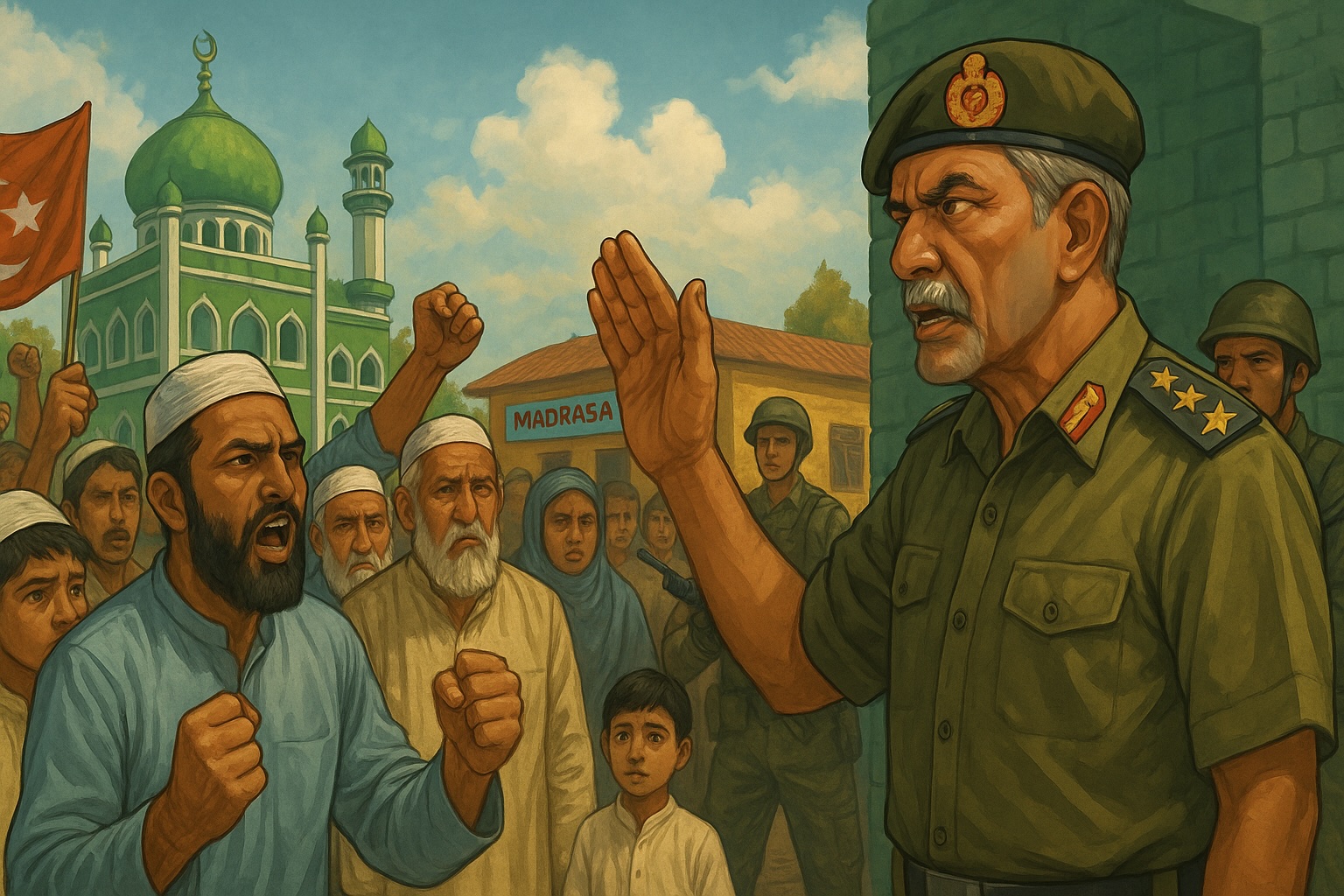

Mosques Multiply Overnight: Are Turkey and Pakistan Radicalizing India’s Backyard via Nepal?

A quiet but seismic shift is underway along the porous India-Nepal border, and Indian security agencies are sounding the alarm. An intelligence report reveals that Turkish and Pakistani-backed religious networks—including mosques, madrasas, and Islamic centers—are mushrooming in Nepal’s southern border districts. What seems at first glance to be a story about religious outreach has, in reality, set off a diplomatic and security firestorm that threatens to reshape the region’s fragile balance.

The heart of the concern lies in the rapid expansion of Turkish and Pakistani influence in these sensitive areas. Turkish NGO IHH (Foundation for Human Rights and Freedoms and Humanitarian Relief), widely reported to have ties to Ankara’s intelligence apparatus and extremist circles, has joined hands with indigenous organizations like Islami Sangh Nepal (ISN). Together, they have funneled resources to build religious institutions that target Nepal’s minority Muslim populations—mosques, madrasas, orphanages, and cultural centers. Turkish support does not stop at charity. Intelligence sources allege that Turkish-sponsored institutions—often under the aegis of the government agency TIKA and shielded by the Turkish intelligence service MIT—are promoting a particular brand of political Islam. The presence of SADAT, a Turkish paramilitary group with known ties to ISN, has heightened suspicions of covert militia training and clandestine activities.

Pakistan, India’s traditional rival, is accused of running its own playbook. The report claims that the ISI has helped finance a dramatic surge in religious structures along the border. In Nepali provinces abutting Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, and West Bengal, the number of mosques reportedly rose from 760 in 2018 to 1,000 in 2021; madrasas from 508 to 645. Many of these institutions, say intelligence officials, are more than just places of worship or learning—they have allegedly become safe havens for extremists and criminals, logistical hubs for anti-India operations, and breeding grounds for cross-border radicalization.

India’s open border with Nepal—a 1,751-kilometer stretch that remains largely unfenced—makes it especially vulnerable. The free movement of people and goods, a long-standing pillar of India-Nepal friendship, has become a double-edged sword. Law enforcement has recorded evidence of financial transfers and logistical support to banned groups like Indian Mujahideen, Lashkar-e-Taiba, and Jaish-e-Mohammad moving through Nepalese territory. Guesthouses and madrasas, intelligence sources claim, have been used to harbor operatives from Pakistan and Bangladesh, providing operational cover and launching pads for nefarious activities.

What alarms Indian strategists even more is the apparent demographic shift in certain border districts. Intelligence agencies say there has been a noticeable rise in Muslim populations in some villages, with mosques and madrasas now outnumbering Hindu religious sites. These changes are interpreted by Indian officials as part of a calculated attempt to establish parallel social structures and build friendly networks that could be mobilized for disruptive ends. The proliferation of religious facilities—most of them unmonitored by either Indian or Nepali authorities—creates fertile ground for recruitment and radicalization, making the border a potential powder keg.

New Delhi’s response is fraught with diplomatic sensitivity. While Pakistan’s role as an adversary is well known, Turkey’s intervention is subtler—mixing humanitarian rhetoric with an ideological push, and projecting itself as a “friend” of Nepal. The dual challenge forces India to rethink its border management, intelligence sharing, and even its approach to relations with Kathmandu. Officials warn that the sheer volume of newly established religious institutions, coupled with the open border, poses serious surveillance and enforcement challenges. The situation is made even more complex by the need to differentiate genuine religious activity from fronts for more sinister designs.

Local populations, meanwhile, remain caught in the middle. For many, the new mosques and madrasas are sources of charity, education, and a sense of community. But for Indian security agencies and some segments of civil society, they have become lightning rods for suspicion, a sign that the borderlands are being reshaped by foreign hands with unclear motives.

As the geopolitical tug-of-war intensifies, India is left to grapple with uncomfortable questions: Can the region’s social harmony withstand this infusion of foreign-funded ideology? Are the open borders of South Asia’s democracies now liabilities in a new era of proxy competition? And what happens if these networks, left unchecked, become conduits for the very extremism India has spent decades trying to keep at bay? The answers, for now, remain elusive—and the stakes could not be higher.

![From Kathmandu to the World: How Excel Students Are Winning Big [Admission Open]](https://nepalaaja.com/img/70194/medium/excel-college-info-eng-nep-2342.jpg)