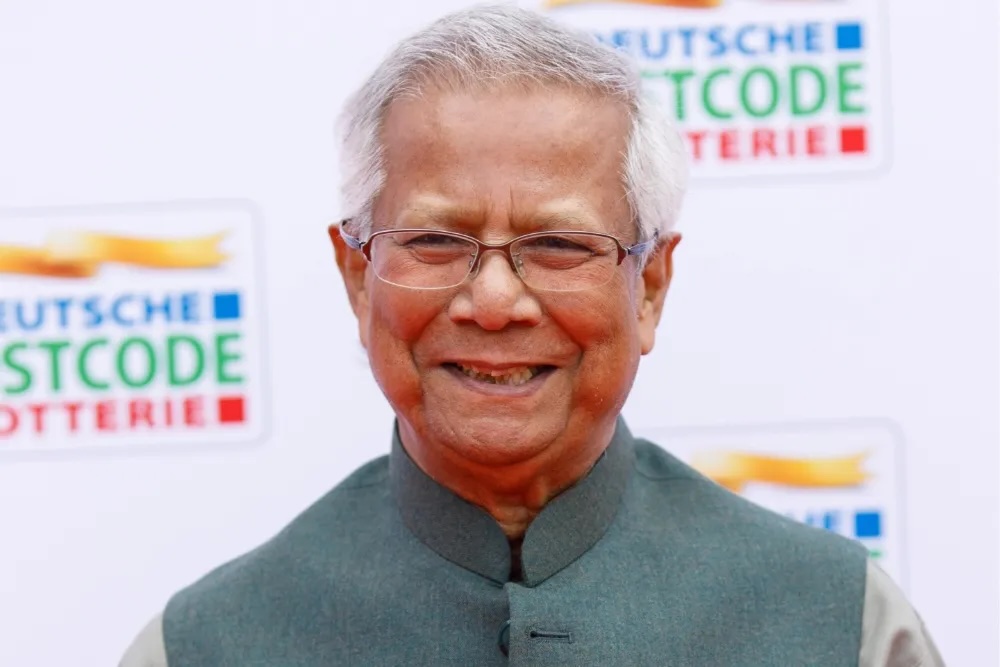

Killing of Hindu community leader exposes deepening minority persecution scenario in Bangladesh under Yunus

On April 17, the body of Bhabesh Chandra Roy, a well-known Hindu community leader in Bangladesh, was found in the Dinajpur district.

Reports confirm that Roy had been abducted, brutally beaten, and left to die—a savage act that sent shockwaves through the nation and across international human rights circles.

For Bangladesh’s Hindu minority, however, the horror is tragically familiar.

Roy’s killing is not an isolated incident but yet another grim milestone in a long history of persecution that has intensified under the interim government led by Muhammad Yunus, following the ouster of Sheikh Hasina.

The murder of Bhabesh Chandra Roy is not just a tragedy for his family or community. It represents a larger pattern of violence, fear, and systemic neglect that continues to endanger the lives and dignity of religious minorities in Bangladesh.

For decades, Hindus in the country have faced a cocktail of threats—social, political, and physical. But the recent transition of power has brought with it a disturbing surge in hostility and impunity that appears to be emboldening extremist elements.

Roy, a respected figure in Dinajpur, was known for his efforts to bridge communal divides and support local Hindu families facing economic and social marginalisation.

His community leadership placed him at odds with powerful forces that view religious minorities not as citizens, but as obstacles or bargaining chips.

The manner in which he was silenced—abduction, torture, and public disposal—was calculated to instil terror, not just to eliminate a voice of reason.

Since Yunus assumed power as the head of an interim government, replacing the long-standing Awami League administration of Sheikh Hasina, Bangladesh has entered a turbulent phase.

While the government was expected to be transitional and technocratic in nature, its inability—or unwillingness—to rein in sectarian violence has raised eyebrows.

In fact, critics argue that the current administration has created a permissive atmosphere, whether through active complicity or sheer indifference, where minorities are increasingly vulnerable.

Under Sheikh Hasina’s leadership, though not without its criticisms, there was at least an institutional acknowledgement of the challenges facing minorities.

Her administration maintained symbolic and sometimes substantive protections for Hindus and other marginalised groups.

The Awami League, with its secular roots, offered a degree of assurance, even if imperfect. But with Hasina's exit, those fragile safeguards appear to have collapsed.

Since the start of 2025, Hindu homes, temples, and businesses have come under heightened attack in several districts across Bangladesh.

Incidents ranging from mob violence to land grabs and targeted killings have surged, often with little follow-up from authorities.

The case of Bhabesh Chandra Roy, where eyewitnesses claim that the police delayed in taking action even after his abduction was reported, has only deepened public mistrust.

There is a chilling message being sent to minorities in Bangladesh today: that their lives, property, and voices carry little weight in the new political order.

Dinajpur, a region with a sizable Hindu population, has now become a hotspot for targeted intimidation.

Local reports cite multiple instances of forced evictions, threats during religious festivities, and extortion—all under the shadow of political instability.

International reactions have been cautious but concerned.

Human rights organisations, including Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, have called for a thorough and impartial investigation into Roy’s death, while the external affairs ministry of neighbouring India also condemned the incident.

However, such appeals often fall on deaf ears in Dhaka, where national pride and political defensiveness overshadow the urgent need for justice.

Moreover, the Yunus government’s diplomatic posture has been one of denial, with repeated claims that communal incidents are being exaggerated or politically motivated.

This habitual dismissal only aggravates the fears of minority communities. When the state refuses to acknowledge a problem, it tacitly allows it to grow.

The failure to publicly condemn Roy’s murder in unequivocal terms speaks volumes. Worse, it suggests a normalisation of the grotesque—a readiness to accept violence as a byproduct of transition rather than a rupture in the fabric of democracy.

For Bangladesh’s Hindus, the emotional toll is immense.

The community, which once made up nearly 30% of the population in the years following Partition, now constitutes less than 9%, a decline that reflects decades of migration, disenfranchisement, and trauma.

Bhabesh Chandra Roy's killing is just the latest reminder of why so many have left, and why those who remain often do so in a state of dread.

Roy’s murder also underscores the shrinking space for civil leadership within minority groups.

When a community leader is assassinated in broad daylight and the perpetrators remain at large, it sends a message not just of fear, but of futility.

The longer this environment persists, the more fragile Bangladesh’s pluralistic identity becomes.

Founded on the principles of secularism and inclusivity, the country risks devolving into a landscape defined by majoritarianism and selective justice.

The interim government must reckon with this reality—not as a footnote in their tenure, but as a central test of their credibility and capacity.

What happened in Dinajpur on April 17 is a national disgrace. It is also a humanitarian warning bell.

Roy's murder is not a single event to be archived and forgotten; it is a reflection of a growing storm that threatens not just one community, but the very essence of Bangladesh’s democratic promise.

![From Kathmandu to the World: How Excel Students Are Winning Big [Admission Open]](https://nepalaaja.com/index.php/img/70194/medium/excel-college-info-eng-nep-2342.jpg)